The Role of Audiologists in Hearing Care & Hearing Loss Treatment

Audiologists are highly trained healthcare professionals who specialize in

Audiologists are highly trained healthcare professionals who specialize in

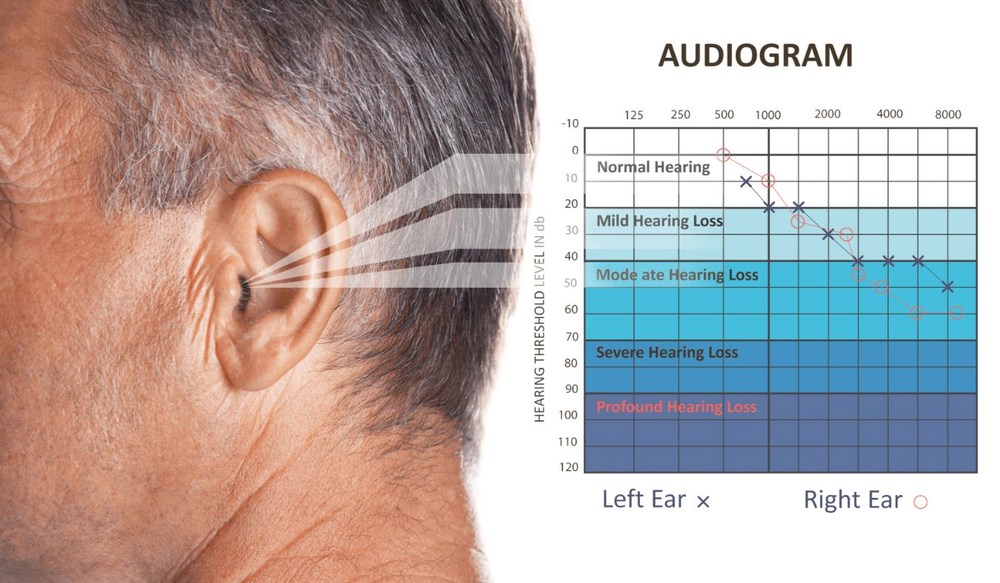

Hearing loss is a common issue that affects millions of people worldwide,

Hearing tests are an essential tool in diagnosing and understanding